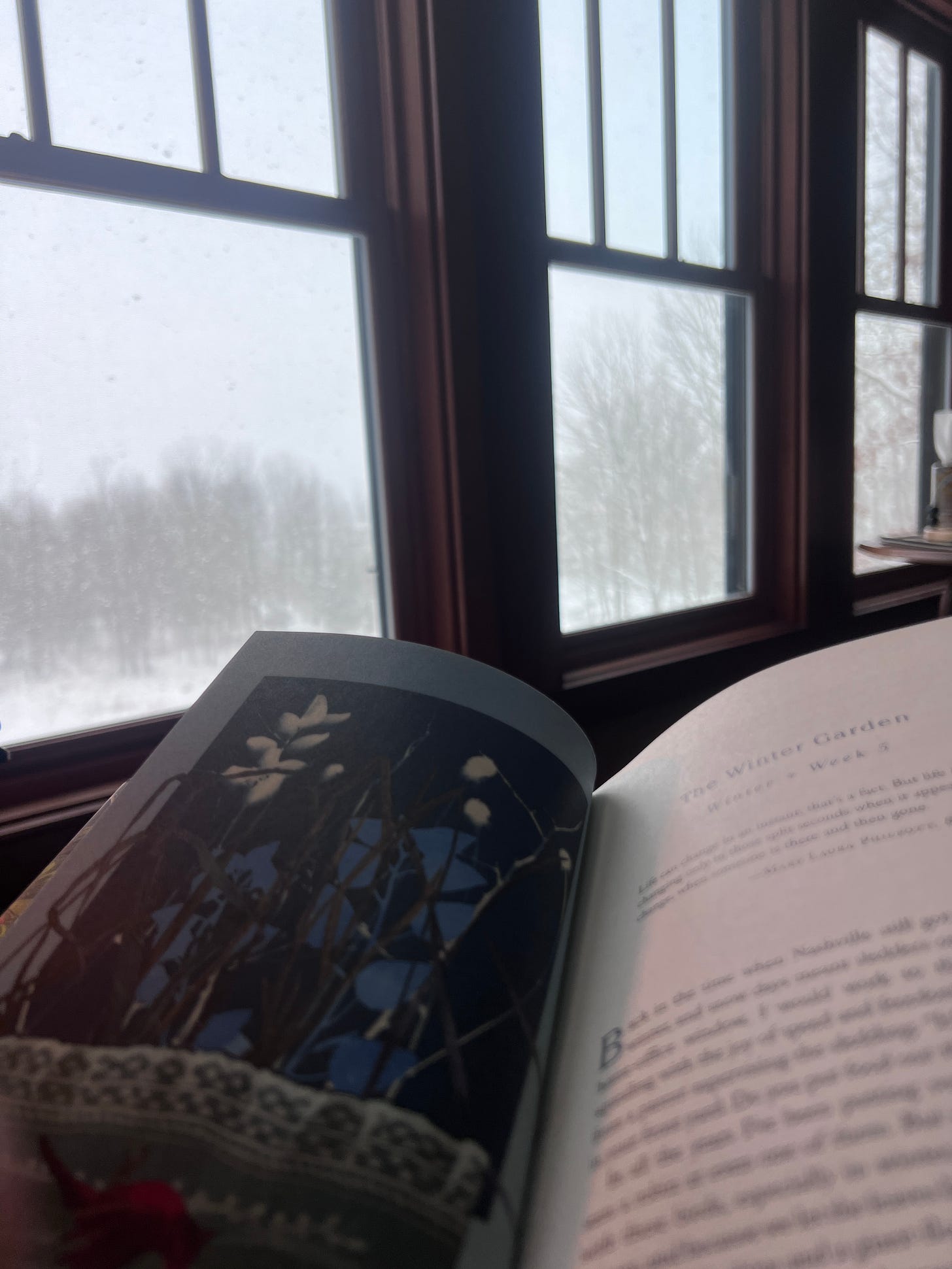

So-Slow Book Club, week 5: in defense of an un-manicured yard

“Year by year, the creatures who share this yard have been teaching me the value of an untidy garden.”

Join us in reading The Comfort of Crows by Margaret Renkl in a low-pressure, year-long book club. This post is free to read, but commenting is for paid subscribers only - upgrade your membership to join in the conversation!

I’ve never been very good at lawn care. By that, I mean the neat-and-tidy, mow-and-edge style demanded by HOAs and expected in neigh…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Kettle with Meagan Francis to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.