Is it time to bring frugality back?

What "The Tightwad Gazette" taught me about paying attention to the small things

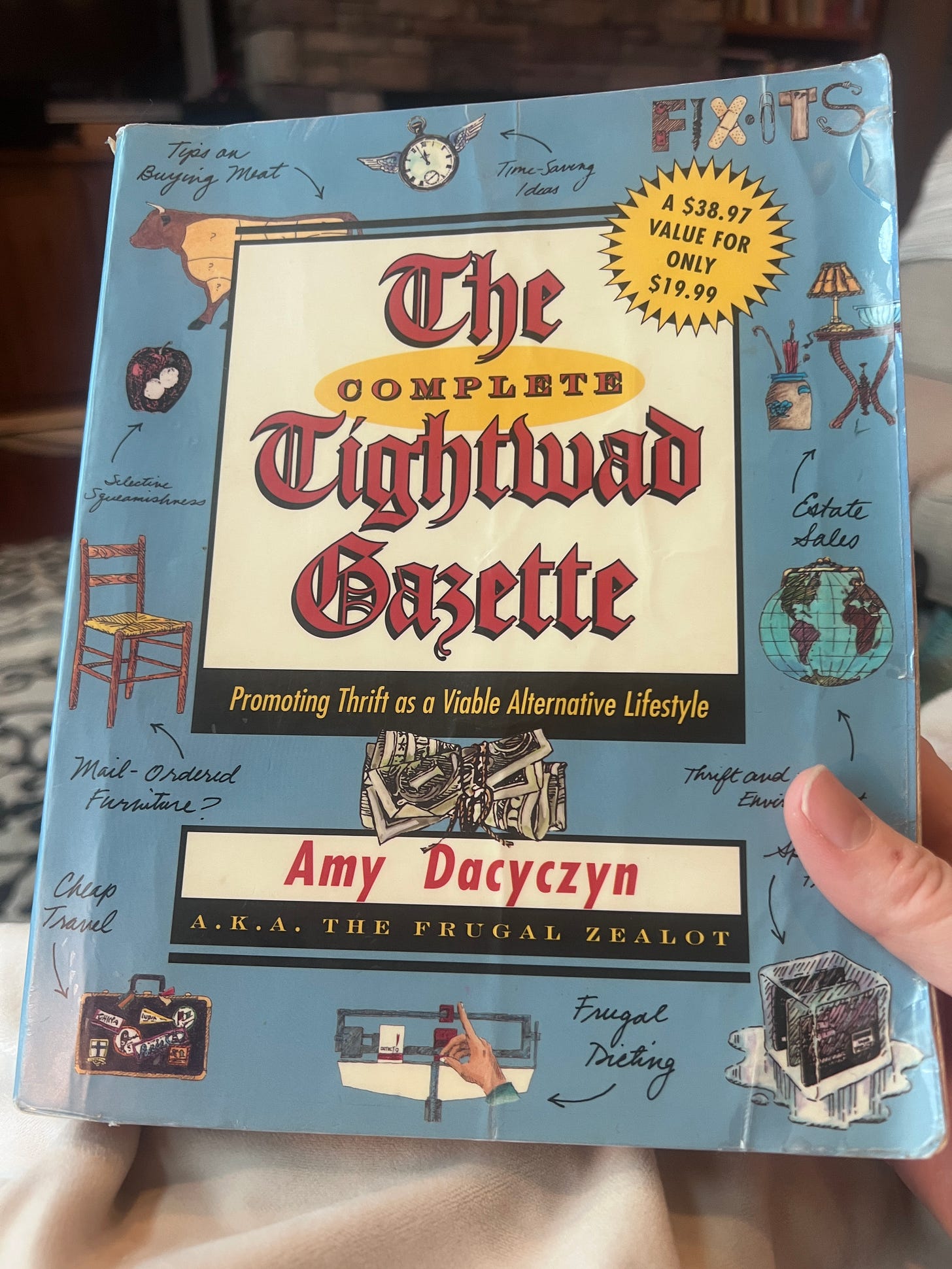

When I was a brand-new, twenty-year-old mom, my sister introduced to The Tightwad Gazette by Amy Dacyzyn, a thick book compiled from her newsletter which had been published through the early 90s.

With very little money and even fewer homemaking or budgeting skills at the time, I pored over these books, soaking up Amy’s advice on everything from re-using aluminum foil to mending clothes to how to get the best deal on a used car.

At the time, myself, my then-husband Jon, and our firstborn Jacob - then just a few months old - were living in my sister’s basement, trying to get established in a new city. I babysat my nieces and nephews in exchange for temporary housing and waitressed on the weekends - that shift meal was a big luxury back then! - while Jon installed cable TV. Our grocery budget was tiny and our “fun” budget practically non-existent: every penny counted, especially during a time when the pennies scrounged under the sofa cushions could still put enough gas in the tank to drive to work.

I had grown up in a very frugal household. My mother - who ran a daycare out of our home to keep our family afloat - wasted nothing, whether it be a dollar or a styrofoam meat tray. But while I’d absorbed Mom’s general tendency toward thrift as a young person, I hadn’t been paying close enough attention to pick up many practical tips. My tightwad spirit was willing, but my abilities were weak: I wanted to be a scrappy reuse-it-or-fix-it-or-make-it-yourself-er, but I just didn’t really know how.

So during nursing sessions and naptimes, I devoured The Tightwad Gazette. Warming to Amy’s humorous, no-nonsense style, I learned about thousands of ways to save money, including canning jam, fixing broken zippers, and baking my own bread.

Amy’s knowledge and dedication to tightwaddery was next-level, and I suppose it would have been understandable if I’d come away with a sense of deprivation, not to mention desperation: you’re telling me that I’m going to have to re-use rubber bands and bread tabs for the rest of my liiiiife?

But the ideas in The Tightwad Gazette represented something more to me than just doing without: they helped me see the world through a lens of abundance- of the things I could do - rather than through a lens of scarcity; the things I couldn’t have (which in those days, happened to be most things.)

The promise of being able to make, fix, or find what I couldn’t buy new - and have fun doing it, as Amy Dacyzyn clearly was - reminded me that even without experience, education, or high earnings, I had options. It was a powerful lesson for me, and looking back over my life I can clearly see that the times I have felt the deepest sense of abundance have been when I’ve felt most tapped into my personal agency, not when I’ve been earning the most money.

I don’t want to romanticize poverty. Being broke is stressful. But then again, being not-so-broke can be stressful, too. Earning more doesn’t always relieve the stress of living close to the edge; often, it just moves the edge, particularly when you’re investing so much time and energy in earning that you start paying for more and more things to help you hold your life together.

And bottom line, no matter how much money I have, spending it has never given me the same feeling of agency and possibility as it has to realize that I can make, do, or repair something myself.

Despite my humble roots, I’m as guilty of mindless spending as anyone, particularly when I’m busier than is really good for me. Our family has been in a solidly middle-class income bracket since my youngest two children were born. And at some point along the way I bought into the idea that I could out-earn having to worry about the “little” things, those small frugal moves, and focus only on the “big” moves - earning, investing, maximizing.

There’s nothing wrong with those things in theory, but it’s also true that focusing so much on those “big” moves made it pretty much impossible to think about all the little things anymore. So, as most of us do at some point, I stopped doing the little things, like reusing foil and sandwich bags, and turned to paid solutions for convenience, comfort, and entertainment.

Big moves were in, small savings were out.

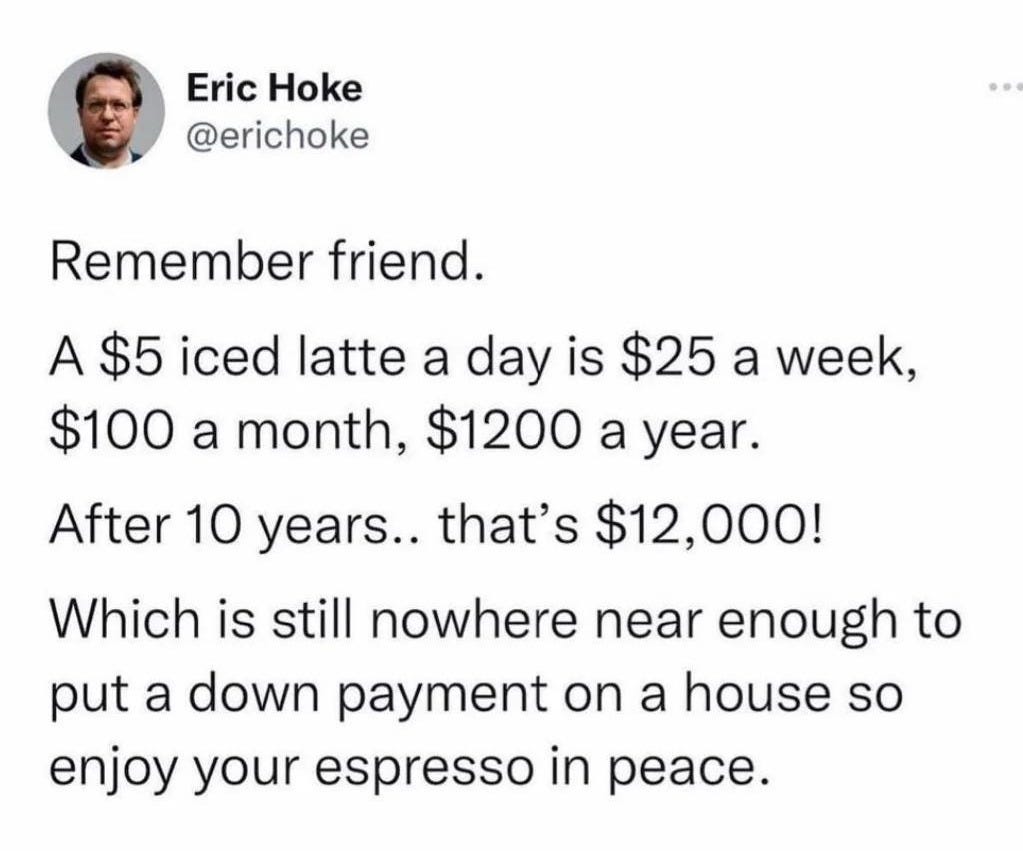

At some point, frugality fell out of fashion - hard. Today’s financial gurus advocate for maximizing earnings and investments instead of worrying about small purchases. Countless memes mock the idea that forgoing lattes will make it possible for a young person to buy a home.

At the danger of sounding like a boomer, I think these memes miss the point, and there’s a fatalism in the idea that small choices don’t matter that strikes me as intellectually dishonest.

Because let’s face it, it’s not really about the $5 latte, or whatever the $5 latte represents to each of us individually. Most of us are not simply indulging in one small convenience or luxury: it’s the latte and the (increasingly expensive and often mediocre) meals out and the closet full of new clothes and all the streaming services and the stuff we didn’t even know existed until we saw it on Instagram.

It’s the idea that we can soothe the stresses of unmanageable modern lifestyles one little “well-deserved” luxury at a time.

I’m not against little luxuries or conveniences - not at all. As an author and small business owner, I want and need people to buy things like books and tea. And spending money on things I value - yes, like books and tea, but also handmade objects, a monthly massage, and lovingly-made or farm-fresh food - feels deep-down good.

But, using the latte example since it’s been so run into the ground, how much does the typical person really care about a paper cup of (I’m guessing usually not particularly amazing) coffee? I am not a coffee drinker, so I truly don’t know. My guess is that to some people it is actually very enjoyable and absolutely worth the money, and that to others, it’s just something they pick up to stay awake or endure the grocery store.

Do you know which category you fall into?

Or, let’s look at an expenditure in which I have more personal experience: streaming services. At one point recently I was horrified to discover that what our household was spending monthly for a variety of streaming services - Spotify, Netflix, Hulu and the like - was considerably more than what once would have been my entire grocery budget.

There’s something about the unchecked and nearly-unnoticed flow of thousands of dollars per year, out of my checking account and into the coffers of billion-dollar corporations (via credit-card transactions that enrich trillion-dollar financial institutions) that made me feel queasy, even if I could technically “afford it.”

The truth is I just don’t care much about streaming services. And spending money on things I don’t care about just because it’s convenient, or everyone else in my income bracket seems to have it, or because one time I felt like watching a show and this service doesn’t cost that much feels…well, kind of gross, if I’m being honest.

It’s been twenty-seven years now since I was first introduced to The Tightwad Gazette, but when I happened across one of the books at my local library a couple weeks ago, I felt an instant wave of nostalgia and, once again, that singularly expansive and abundant feeling.

So I checked it out, and I’ve spent my mornings poring over it.

Not all of the circa-1990s tips have held up well for a 2020’s reality, and the 90s prices have made me laugh out loud a few times, but the scrappy wisdom still shines through.

I have also been delighted to see, decades later, how much of Amy’s wisdom stuck: I can give The Tightwad Gazette the credit for so many practical, frugal practices that have been a regular part of my life for decades, and I can also see where the book planted the seeds for many other skills that I’m now finally trying to learn and incorporate. I have still never repaired a zipper, and I didn’t start baking bread regularly until I was 47 years old, but re-reading The Tightwad Gazette reminded me that it’s never too late to start.

Over the years as a self-employed person I’ve had years where I earned very little, and other years where I earned quite a lot - for me, at least. But earning and spending has never given me the same feeling of agency and possibility as it has to realize that I can make, do, or repair something myself, or simply go without.

What I’m remembering now is that the real reason this book spoke so strongly to me way back when, as a poor, young mom. Amy Dacyzyn wasn’t selling a clear-cut program to making X dollars on your investments, but instead, encouraging a different way of viewing the world.

She didn’t argue that you should adopt every single idea in her book, nor did she claim that reusing baggies would fully fund your retirement account. It was more about mindset; the idea that small things were worth paying attention to; that when taken together, these little practices could add up to real savings, and best yet, that living with this mindset - however it manifested in one’s particular household - could be richly rewarding, creative, and even fun.

Looking back now in my “big money moves” era, I can see the many ways I bought into a trap: that if I earned enough (via the consumer economy) and invested back into that same economy, I would be rewarded with not only long-term stability, but the ability to indulge in all the conveniences and comforts (also purchased through said consumer economy…see where I’m going with this?) that would hopefully make the tradeoffs tolerable.

Re-reading The Tightwad Gazette - and reading between the lines with the benefit of age and experience - I can see that what Amy Dacyzyn really wanted most of all was freedom: to be able to live her life on her own terms, by rewriting the script of what “modern life” demanded of her. She achieved that goal through pro-level frugality, taking it further than most would likely ever want to. My path will be my own. But I have more agency over it than I always stop to remember.

I’m feeling ready to recommit myself to a different way of thinking about money, a way that’s a little closer to my roots. A sort of “poorer on purpose” mentality that prioritizes a free and frugal lifestyle over maximizing earnings.

There is much financial uncertainty right now, and many things we can’t control about how our fragile system will ultimately play out. I know this one thing for sure: I can’t beat the billionaires at their own game. The house always wins, friends.

But I can play a different game. I can decide what kind of life I want to create for myself in all of this, determine what matters to me and what doesn’t, which rules I play by and which ones I’m willing to throw out the window. I can remember that experiencing a feeling of abundance has very little to do with what I can buy, and is much more about the posture I bring to the world; a willingness to reexamine my priorities and, yes, my purchases.

And maybe, just maybe, a willingness to consider re-using aluminum foil once again.

About me:

Hi! I’m Meagan, an author, podcaster, and midlife mom of five (mostly grown) kids. Here at The Kettle, I share my thoughts on how to live wisely and well in a manic modern world. While new posts are free, paid subscriptions help me continue to create here - and if you want to connect more deeply, the private chat is open to paid members. I appreciate you!

I love this perspective so much.

I still have a jar of rubber bands, and the jar is one of the decorative glass jars the Boy Scouts sold popcorn in in the 1970s. We've definitely returned to some of our money-saving habits; some we never stopped after living through pretty lean times in the 80s.